Wallada’s father was the eleventh caliph of al-Andalus from 1024 to 1026, when he was assassinated. She lived during the beginning of the decline and disappearance of the Umayyad dynasty and the civil war that ends with the division into multiple kingdoms. She trespassed the period’s behaviour limits for women of her lineage, by convening literary meetings and composing poetry and satires. She died on 1091, the same day that the Almoravides conquered Córdoba. She was a witness of the fall of al-Andalus.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I feel the need to make a clarification before beginning with the story. We must bear in mind that the biographies of Arab women are very scarce. Just being named collided head-on with a society that demanded modesty and decorum, and kept women confined to the space of men’s private life. Actually, their voices are always heard through men. Men were expected to be the only ones who wrote poetry or literature. If a woman was named, it was typically by the man who added something at the end of his writing, like something that was considered irrelevant. If a woman composed a poem, it was placed at the very end of a man’s piece. And sometimes, the man had the right to change the woman’s texts.

In Wallada’s case, most of the details that are told about her life belong to the field of myth and legend. It is very difficult to find reliable sources. On the Internet there is a lot of disinformation that mixes up different people who have the same or similar name. It seems relevant to me to make this note because if some readers do some research, they will find contradictions with what I’ve written. I would like to point out that the stories narrated by Wallada are based on the few sources that we know are from the same period (not from later centuries), and that are studied by María Jesús Viguera or Teresa Garulo Muñoz, among others, specialists in poetry and women of that historic moment. In their works they try to remove the features that have been added to her personality in the last centuries and highlight that she was undoubtedly a woman ahead of her time, with a strong personality, but there is no evidence that she was maneater, who was free and open sexually with both sexes, who did not wear a veil (hijab), or continually confronted men. From some texts that appeared three centuries later in Egypt, a character was created who is far removed from the reality of the moment. And over the last thirty years, other more contemporary features have been added to her personality: details that belong more to a woman of the late 20th century (1). And without further ado, Wallada begins to narrate:

I have had to live in this decaying period. Since I was a kid, people always told me about the splendor of Córdoba, of its palaces, of its people. And I have only experienced endless coups d’etat by the worst Umayyads (2): none has been a worthy successor to the first caliph or, if we go further back, to the brave wiseman, Abderrahman I “the immigrant,’ who started everything by fleeing from Damascus.

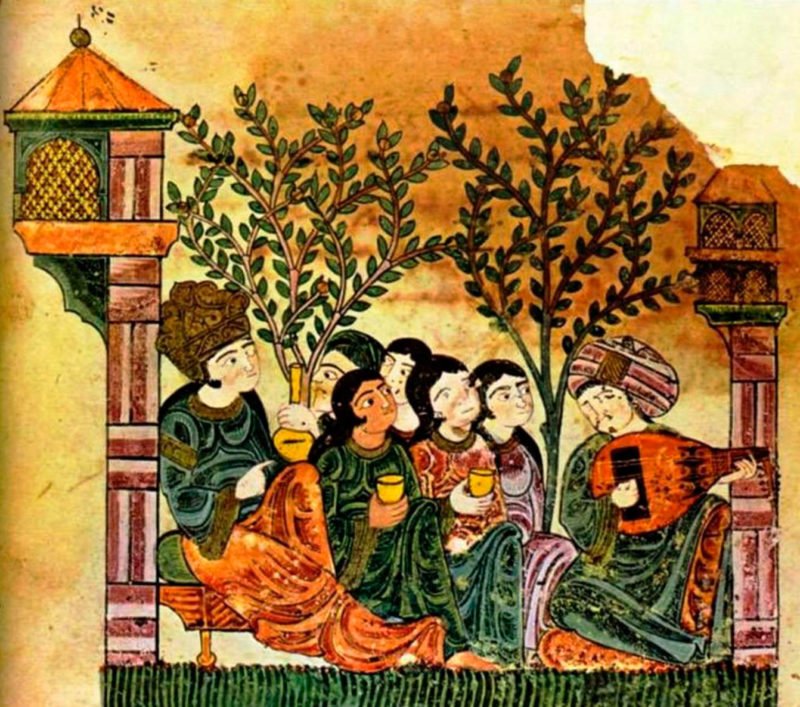

I cannot complain about my life. The women of my class at this time are silenced and hidden. I was able to be reckless and I’ve crossed lines that no woman had dared to cross. I have never understood that if I liked poetry, it would be disrespectful to dedicate myself to it and enter into gatherings with other poets. I was never forgiven for composing verses together with other poets. And what is more important, to overtake the most distinguished ones. I myself made them talk about me, and that is the worst imprudence a woman can commit. The other was, without a doubt, not getting married and showing, without remorse, the culture and knowledge that I possess.

Fortunately, my mediocre father had a fortune that allowed me to live without having to give myself up to a marriage. But for Córdoba standards, I will always be the whore that opens her house for poetic and philosophical readings. Even when I fulfill the etiquette that corresponds to my lineage and name, and I maintain irreproachable conduct, they talk about me. And in this society if you talk about a woman, it is never for the best. We all must do what is required of us due to our good lineage: wear the veil to avoid being recognized; surround myself with slaves who hide me when I go to pray to the mosque; and if I see any man, withdraw immediately, scared, so that he won’t be able to compose verses about me, or God forbid, he would ever name me.

I have always refused such denigration of my intelligence. Loving poetry has always been a risk to our honor. And I’ve never stopped wondering why. What could be the problem of laudatory verses dedicated to someone. And it is simple: the problem is that it was assumed you had lovers, causing you to be disowned. But, once my father died, I had no one who could disown me. I had my family who protected me, but no one who could disown me. And I could follow the norm, but I liked culture and poetry too much and I was not going withdraw from my gatherings.

It has also been my way of rebelling to the changing situation, in which there are no legitimate powers. Because we haven’t had a strong, legitimate leader in a long time. My dear Ibn Hazm, one of my protectors and my master in poetry, is right, when he defines my incompetent father as the worst caliph. It never ceases to make me laugh that he chose as his name “the one who is satisfied with God”, when he got the throne, when he did not stop being behind intrigues and was only looking for power and the title of caliph. Hypocritical and a coward, his escape was such a blunder that he was found and killed. Of course, the world did not lose anything valuable. And perhaps his life was only really useful for me, by giving me a position when he got my mother, a slave, pregnant.

Today I look back and see how his fortune and lineage helped me not to have to be another woman of the nobility, hidden from the eyes of everyone, nor to depend on any man. Thanks to him, I had protection that allowed me certain eccentricities. I did not live the splendor of my lineage, of the Umayyads. I did not get to see its greatness. I have only been able to witness its decline and collapse, the breaking into pieces of what was al-Andalus. I could even see how the last Umayyad caliph was eliminated and replaced by another government. And as a final touch to this dramatic end, Córdoba, which was the largest city ever known, is right now besieged by enemy troops, barbarians from across the sea, the Almoravids. And it won’t be able to last much longer. Me neither.

(1) Arab women in the Middle Ages: private lives and public roles by Manuela Marín analises this.

(2) After three centuries of great splendor, the 11th century, is distinguished by unstable governments which endure just few months between coups d’etat, a neverending civil war, confusion and continuous confrontations between the Umayyads and different parts of the dynasty.