Anton van den Wyngaerde is one of the historic figures in this blog fictionalized by Blanca based on her research that

includes primary sources. If you want to know about this series of tales, please click here.

Anton van den Wyngaerde, from the Netherlands, was a prized and sought-after 16th-century draftsman, whose specialty was making chorographies, geographical descriptions of a región. He dedicated himself to drawing cities in such a way that the most notable buildings and structures could be appreciated as well as the surrounding área and agriculture. He was hired by Felipe II to draw the most important cities in Spain to create an atlas.

Anton van den Wyngaerde, from the Netherlands, was a prized and sought-after 16th-century draftsman, whose specialty was making chorographies, geographical descriptions of a región. He dedicated himself to drawing cities in such a way that the most notable buildings and structures could be appreciated as well as the surrounding área and agriculture. He was hired by Felipe II to draw the most important cities in Spain to create an atlas.

Author’s Note: Wyngaerde will describe how the almadraba (traditional fishing traps) worked in the 16th century. There have been different ones throughout the centuries and this one was called de tiro, the shooting one. The art of almadraba has changed over the centuries and nowadays it is much less aggressive so the tuna do not suffer and it is considered the most sustainable form of fishing that exists. The Almadraba have been recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage and are not only a fishing technique. For over three thousand years they have forged a society and shaped settlements and entire towns in the areas close to the Straight of Gibraltar to make the unique landscape along the Atlantic.

Anton van den Wyngaerde’s diary, March 20, 1567

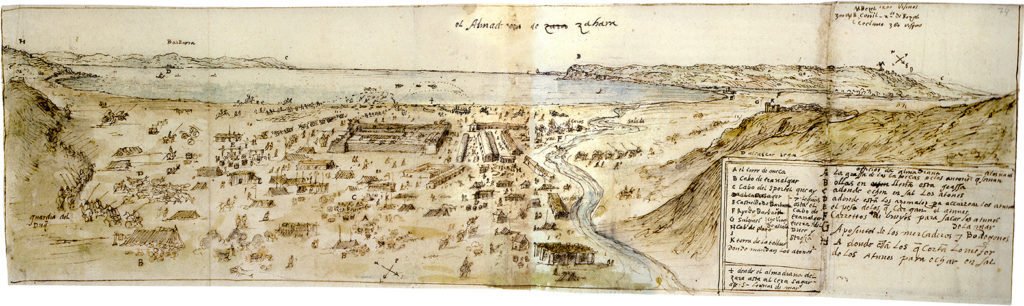

When I was commissioned to draw cities and towns in Spain for His Majesty Felipe II, it was pointed out, with great vehemence, that no matter what, I had to come here in March to this beach. I did not understand why until today. A beach?, I asked myself. What an extravagance. I did not get it. Mainly, they wrote and strongly insisted that I draw the al-ma-dra-bas, almadrabas (traps), in great detail. A strange name that I find even difficult to pronounce and did not have a clue what it meant. A beach, without any city or a battle to draw. Just a beach and fishermen. I could not understand what interest the king might have in getting something like that documented.

And today I understand it perfectly. It is impossible to describe the spectacular nature of what we are experiencing here. In fact, I don’t know which is more impressive, what is happening on the shore with the fishermen, the boats, the fight with the tuna or what I am seeing on land between workers cutting and hanging tuna and the songs, the music and the party the Duke of Medina Sidonia has assembled. Two thousand people, making a crazy racket that is impossible to understand if we do not start with what tuna means to this society.

Almadraba, an ancient fishing technique

It seems that since the conquest of these lands from the Muslims in the 13th century, tuna fishing is controlled exclusively by this duke. And from the tuna, everything is useful. It is one of the most profitable fish. I have been told that in winter the tuna are in the North Sea, in cold waters, eating and gathering strength. And when spring arrives and they accumulate more fat, they go down to the Mediterranean, because the tuna can safely spawn at the bottom of the warmer waters. Here in the Strait of Gibraltar, the entrance to the Mediterranean, killer whales await eagerly for the tuna. That is why the tuna stick to the shore before crossing this strait, to try to outwit the killer whales. But of course, when the tuna get close to the shore, some are caught.

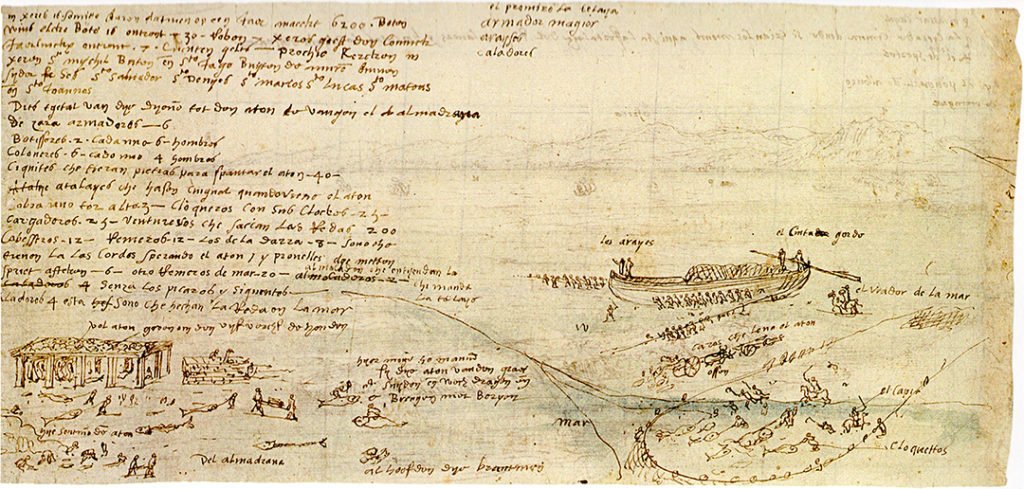

We are talking about a kind of fish that is like a bull that can reach 500 kilos (1,100 pounds). Real beasts that swim very fast. The almadrabatechnique is based on using nets and men to cut off the path of the tuna. Imagine how it is. I have been told that the strange word almadraba means “place where to hit or fight”. It is just that. I don’t believe what I see. And that’s what I’m drawing. How they are organized, how they are prepared and how the final blow is carried out against the group of giant fish. They tell me that this fishing system comes from the Phoenicians. I’m going to try to explain the phenomenal show I’m attending, because it could be classified as superhuman.

During my stay, the councils of each area are ordered to assign a trustworthy person to help me with the local people and to tell me, while I draw, the names of the hills, buildings and to help me understand what I am seeing. I never thought that my assistant here would be the VII Duke of Medina Sidonia himself, Mr. Alonso Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno.

It seems that in his family, it is a tradition to come and see the work of the almadrabas as it begins. And it is common for young and strong children to train with the fishermen to be tough and brave. And you bet the current Duke of Medina Sidonia is tough and brave. This man can be singing and watching the dancing, but as soon as he hears they see tuna in the distance, he runs to the shore to help his men catch these huge fish and he pounces on them himself. Not in vain do they call him ‘The God of Tuna.’

Parece que en su familia es tradición venir siempre a ver el inicio del trabajo de las almadrabas y es habitual que los hijos jovenes y fuertes, trabajen con los pescadores para curtirse. Y vive Dios que el actual duque de Medina Sidonia está curtido. Este hombre tan pronto está cantando y viendo bailar, como oye que avistan atunes y se va a la orilla a ayudar a sus hombres a cogerlos y se lanza como otro más contra esas bestias. No en vano lo llaman el Dios de los atunes.

Boats, nets and two thousand men: the almadraba de tiro

It is not easy to understand how the almadraba work. But if it can be summed up, I would say that nets surround a school of tuna. Then, twenty-five men bravely jump among these animals, each weighing up to 500 kilos, to catch them by the head with the curved knives (cloques) they carry and drag them to shore. There are six boats in the sea, linked with nets to shape an arch. There is a series of watchtowers along the coast to sight the tuna and watchmen warn each other with signals. Flags from these towers are used to signal boats and groups of fishermen where the tuna are located and what they must do to fence them in.

The blow is brutal. Tuna, huge and fast, hit the nets, and try to push them or to jump them. To avoid this, stones are thrown at them while another boat comes from land and locks them up with another very thick net, the jabega. This net ends in two ropes which are controlled by two hundred men from the shore. This is the way the tuna are brought to the beach and as they get closer, with the water reaching the men above the waist, the men strike with the curved knives that go through the heads of the tuna and while they twist, the tuna are dragged to the beach. The cloquers’ strength (the men with the curved knives, the cloques) is enormous.

It is superhuman, they are like twenty-five Hercules standing out in the sea in battle with the tuna. There are tuna jumping, blood, men with unimaginable strength fighting against them, and the wáter red. That is the picture I would like to paint and give to the king so he knows the feat these men accomplish every year.

On the coast, brute force continues as the two hundred jabegueros keep the fence stable despite the force of the tuna. Two hundred men. I feel I am seeing a mythological battle. The tuna caught by the cloquers are taken out of the sea by carts pulled by oxen on the beach. They are piled on the shore to be chopped, some parts are put in the shade, and others are packed in barrels to travel.

The duke, a cloquer himself, who is seventeen and has plenty of strength, proudly tells me that there is no greater intensity in life than fighting hand-to-hand with animals of this type. But he also tells me about the wealth that tuna provides. They have caught up to 100,000 tuna per year for several years in a row between the trap in Conil and this one in Zahara. I am still here drawing from on top of the Zahara castle which is perfectly outfitted for the duke and his guests. I am witnessing one of the most impressive things I will ever see in my life.